Now that the Paris climate agreement has been signed, the hard work begins: Countries have to figure out how to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions without crippling their economies.

Already in the U.S., the state of Maryland is pursuing aggressive emissions cuts. Experts are watching for signs of economic harm, but so far, they have not seen them. In fact, some studies show economic benefits.

Supporters see Maryland as a model for how to transition from fossil fuels while fueling growth. But opponents are not easily convinced.

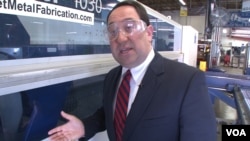

At the Marlin Steel plant in Baltimore, metal parts are made for pharmaceutical companies, carmakers and others. Bucking the trend of the last few decades, Marlin ships products made with American steel to China.

"We'll have a Chinese shipping clerk in Shanghai opening up a box that says, 'Made in America,' " plant owner Drew Greenblatt said. "I'm so proud of that."

Greenblatt says his power bill runs around 7 to 9 percent of his total sales. So when the U.S. Supreme Court froze President Barack Obama's Clean Power Plan, the centerpiece of the administration's efforts to fight climate change, he called it a "wonderful development."

A price on carbon

The rules, which would have increased energy costs, focused on power plants. States would have had to craft plans to cut their emissions. One way to comply was to charge utilities for the carbon dioxide their power plants produced. Many economists say putting a price on carbon is the best way to tackle pollution because it creates a financial incentive to cut emissions.

But Greenblatt says that could raise his costs. And that's bad for business.

"That's the difference between us winning and losing several jobs a year, which means we'll have less people here at the factory," he said.

Thirty-one people work alongside the machines, and the factory is in the middle of an expansion that aims to add another 10 to 15 employees. "We want to hire more people," Greenblatt said. "If you have your costs going up, you can't win more jobs."

Greenblatt cites a coal industry-sponsored study that says power prices will go up more than 10 percent nationwide under the Clean Power Plan. EPA predicts less than 2 percent.

What Greenblatt doesn't acknowledge is that Maryland is already part of a multistate program that charges power plants for their CO2 emissions.

The nine-state Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, or RGGI, funnels revenue from those sales into efficiency programs, renewable energy, reduction of consumers' electric bills and more.

Faster growth

The nine states in RGGI have seen their economies grow faster than those in the rest of the country, even as their greenhouse gas emissions have fallen more than in other states.

According to an analysis by the Arcadia Center, an advocacy group, RGGI states' gross domestic product grew by more than 21.2 percent between 2009 and 2014, while other states' GDP grew 18.2 percent. At the same time, RGGI emissions dropped by 35 percent, compared with 12 percent in other states.

And power prices are flat or down since the program began.

"So far, our economic experts have not seen a significant negative impact on the economy," Maryland environment secretary Ben Grumbles. "[There have been] positive impacts, with more jobs and economic development to come."

RGGI funds have pumped about $2 billion into the nine states' economies.

Grants from Maryland's share of the pot have gone to pay for "green job" training programs in renewable energy installation and home efficiency.

A clear step up

Joel Allen got free job training through Baltimore nonprofit Civic Works. He says it would have cost him $15,000 to get certified through a community college program.

He went from working at grocery chain Food Lion to performing energy audits and efficiency upgrades with a Maryland company called Elysian Energy.

"I was working [for] minimum wage and now I'm [earning] more than $40,000 [per year]," he said. "That's definitely good for someone my age, just 22 years old."

"These types of policies are neither job creators or destroyers. They're job shifters," said Brian Murray, head of economic analysis at the Duke University Nicholas School of the Environment.

And at the price RGGI puts on carbon dioxide emissions, currently around $5 per ton, "the net impact on the economy is just about indiscernible. It's not leading to massive surges in employment growth or massive surges in unemployment."

Those prices are expected to rise as the program tightens greenhouse gas allowances. "Will this put a crimp on economic activity? Most economic modeling suggests no," Murray said. "But only experience will bear this out."