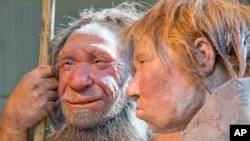

Scientists have long speculated that the early weaning of human babies gave homo sapiens an evolutionary advantage over Neanderthals. Now they may have discovered a way to prove the theory.

New research indicates that the level of barium measured in teeth corresponds with increased breastfeeding.

“People have speculated that an early weaning process in modern humans may have been part of their evolutionary advantage,” said Tanya Smith, an associate professor of human evolutionary biology at Harvard University in a statement. “We don’t have the data to answer that question yet, but we now have the method to be able to start collecting that data.”

According to the study, shorter nursing periods could have led to higher reproductive rates among modern humans.

By studying barium levels, “the timing of breastfeeding and the weaning process can be uncovered in tooth crowns – down to nearly the day,” according to the research, which was published in the journal Nature.

Teeth develop in a similar manner to trees, growing in regular layers made up of various minerals and small amounts of metals, like barium. By studying the barium levels in the layers of teeth, researchers were able to show that barium levels increase dramatically when breastfeeding begins and then fall off as infants begin eating a more varied diet.

Researchers first showed that barium levels correlate with breastfeeding using data from humans and monkeys whose infant diets were well documented.

“We can see when the barium shows up in the tooth after birth, and we see it increase over time, because an infant will take more milk as they get bigger and more active, and then you see it drop off in this beautiful, inverted U-shaped function,” said Katie Hinde, an assistant professor of human evolutionary biology at Harvard.

The methods for measuring barium levels could also be used on fossilized teeth.

“This is a game-changer in many ways, because this will allow us to go to museum collections and look at this as a proxy for how much milk different infants got from their mothers, and what their weaning process was like,” said Hinde. “We can now look at that within species, but we can also look at that among species. That will tell us about the evolution of how mothers invest in their young.”

Smith adds that the research could lead to answers about other developmental differences between humans and Neanderthal.

“What does it mean that human and Neanderthal cranial development was different? What does it mean that their dental development was different? We haven’t been able to get at these questions in the fossil record, but now we can actually get at a real developmental benchmark. That’s why this is so exciting,” she said.

New research indicates that the level of barium measured in teeth corresponds with increased breastfeeding.

“People have speculated that an early weaning process in modern humans may have been part of their evolutionary advantage,” said Tanya Smith, an associate professor of human evolutionary biology at Harvard University in a statement. “We don’t have the data to answer that question yet, but we now have the method to be able to start collecting that data.”

According to the study, shorter nursing periods could have led to higher reproductive rates among modern humans.

By studying barium levels, “the timing of breastfeeding and the weaning process can be uncovered in tooth crowns – down to nearly the day,” according to the research, which was published in the journal Nature.

Teeth develop in a similar manner to trees, growing in regular layers made up of various minerals and small amounts of metals, like barium. By studying the barium levels in the layers of teeth, researchers were able to show that barium levels increase dramatically when breastfeeding begins and then fall off as infants begin eating a more varied diet.

Researchers first showed that barium levels correlate with breastfeeding using data from humans and monkeys whose infant diets were well documented.

“We can see when the barium shows up in the tooth after birth, and we see it increase over time, because an infant will take more milk as they get bigger and more active, and then you see it drop off in this beautiful, inverted U-shaped function,” said Katie Hinde, an assistant professor of human evolutionary biology at Harvard.

The methods for measuring barium levels could also be used on fossilized teeth.

“This is a game-changer in many ways, because this will allow us to go to museum collections and look at this as a proxy for how much milk different infants got from their mothers, and what their weaning process was like,” said Hinde. “We can now look at that within species, but we can also look at that among species. That will tell us about the evolution of how mothers invest in their young.”

Smith adds that the research could lead to answers about other developmental differences between humans and Neanderthal.

“What does it mean that human and Neanderthal cranial development was different? What does it mean that their dental development was different? We haven’t been able to get at these questions in the fossil record, but now we can actually get at a real developmental benchmark. That’s why this is so exciting,” she said.