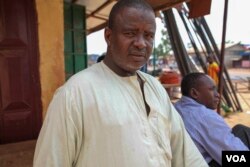

Fred Yokossa works at a bakery in a Muslim neighborhood, alongside fellow Christians who take orders from a boss who is Muslim.

This type of workplace is practically unheard of in the Central African Republic today. Years of sectarian fighting has split the Muslim and Christian communities so thoroughly that the few thousand Muslims left in the capital are confined to just one neighborhood.

Grenade-hurling militiamen wait along its edges. Christians who go in, or Muslims who try to leave, do so at their own peril.

Thousands have been killed and hundreds of thousands forced to flee the country since the sectarian conflict began in 2013.

In C.A.R.’s west, the few Muslims remaining are mostly confined to enclaves like Bangui’s PK5 neighborhood, which is home to the bakery where Yokossa.

Bakery owner Rahama Atthir Abdoulaye said that despite the city's division, people in C.A.R. need jobs, and he sees no problem with hiring Christians.

“I can’t bring a foreigner here to work, no,” Abdoulaye said.

Militias attacked

The former merchant lost his home and his shop in 2013 after militias known as the anti-balaka attacked the capital. They were looking to oust the Seleka rebel coalition, which had taken control of the country earlier in the year.

In their brief time in power, Seleka fighters looted and killed with impunity across the country. The anti-balaka militias were formed in response.

In December, the anti-balaka attacked Bangui, and the Seleka leader was eventually forced out of the presidential palace.

The Seleka leader was a Muslim, as were many of the group’s fighters. Muslims were seen as having benefited from the Seleka’s rule.

As the anti-balaka swept across the countryside and into Bangui, they retaliated against the country’s Muslim minority. Many of the militia’s fighters are Christian.

With his livelihood destroyed, Abdoulaye fled to neighboring Chad, but came back in early 2015 and took over the Boulangerie R.C.A. on Avenue Barthelemy Boganda, one of the main roads into PK5.

The avenue is lined by U.N. peacekeepers who try to keep the Muslims in the neighborhood from clashing with the anti-balaka that ring its edges.

Dignitaries like U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon and Pope Francis have visited PK5 and called for peace.

But the violence goes on. Human Rights Watch reported last month that more than 100 people had been killed around PK5 since the end of September.

Many observers believe the next chance for the country to achieve peace is when a new president is chosen in elections scheduled for December 27.

'We don't kill'

When Abdoulaye moved back to the city, he saw no problem with hiring Christians who came looking for work.

“It’s not necessary to exclude Christians because we don’t kill,” he said.

Yokossa was one of those Christians. He left his job selling cigarettes on Bangui’s sweltering avenues for work at the bakery.

But he has to sneak out of his neighborhood every day to get there.

“I can’t tell my Christian friends that I’m coming here to work. I just come and work, make my money and come back,” said Yokossa. “We’re making money here. How can we kill each other?”

A brief moment of rapprochement between Muslims and Christians in Bangui occurred on the last day of the pope’s two-day trip in November.

After Francis’ visit to a mosque in PK5, young Muslims on motorcycles streamed out of the neighborhood and into the city center, heading for a stadium where the pope was celebrating Mass. Muslims nowadays are rarely seen outside PK5.

But the city at the time was heavily guarded because of the pope’s presence, and the detente was short-lived. The day after, a Muslim was killed near the neighborhood’s edge.